by Hannes Engelbrecht

During discussions in the physical leg of the Heriland Short Intensive Course, I was introduced to the Historic Landscape Characterisation (HLC) approach, which presented me with some real possibilities in terms of academic and practical opportunities. My reflections have explored the applicability of such techniques in a South African context. It also raised several general questions regarding the dichotomies in heritage discourse that persist between tangible heritage and intangible meanings, the treatment of culture and nature as discretely separate, and the notion that Western and indigenous are necessarily antecedents. What features are acceptable characteristics? Is it only tangible human interventions in a landscape that can be characterised as “Historic”? Or is there a place for intangible cultural association with natural features? Is HLC perhaps a discipline-specific Western concept that does not apply in an African context? Or does the possibility exist of marrying philosophies that can improve heritage practice in both cultural contexts?

Two recent cases in my context reminded me of several aspects related to this dichotic thinking. These cases have many divergent political, historical and contextual complexities associated with South Africa’s diverse landscapes and heritages, most notably, their cultural origin and tangibility. However, the two cases intersect in the botanical, horticultural and medicinal uses of the environment in the Pretoria/Tshwane area.

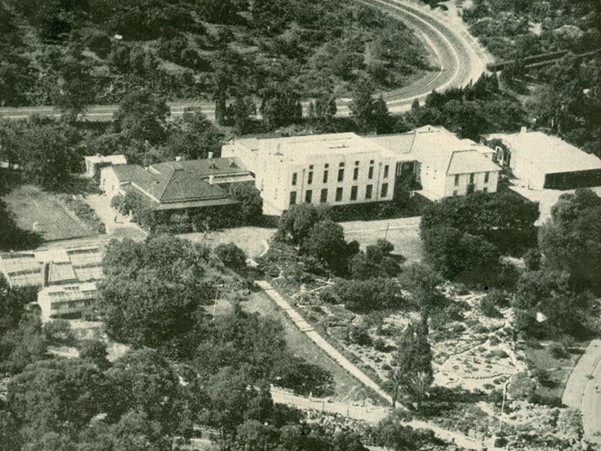

The more tangible of the two cases are the glasshouses at the Union Buildings in Pretoria, which were illegally demolished in 2016 by a South African government department (Figure 1). The notion of illegal demolition of heritage also conjures questions about the practicality of top-down heritage approaches, particularly legal instruments. The iron and glass structure, constructed in the 1920s, served as part of the city’s first botanical garden, National Herbarium and apiary that forms part of a long narrative of the city as an agricultural and botanical hub that features both indigenous and foreign species of fauna and flora and their uses (Figure 2).[1] Although perhaps sad and in need of mourning, the greenhouses were already in an advanced state of decay in the 1980s.[2] They are also part of the greater landscape of the Union Buildings as the administrative seat of governance of South Africa. Due to the complexity of the site, the heritage value of the natural and botanical features has not consistently been recognised.[3] Had HLC been used in the Union Buildings conservation management plan in a more multidisciplinary fashion, perhaps the greenhouses would have been identified as a significant feature.

Figure 1: Image of the glasshouses taken by C. Schutte, circa 2016.[4]

In the South African context, the heritage focus seems to still be mainly on the in situ conservation of heritage structures in that public discussion around the demolition of the greenhouses centred on reconstruction as a conservation method.[5] By characterising the many-layered heritage features of a landscape through HLC and adopting a landscape and spatial approach to heritage planning, perhaps alternatives such as the adaptive reuse of the greenhouses and surrounding structures, as proposed by Thomas Honiball in 2010, would have been more seriously considered.[6] It is less often recognised in a South African context that dilapidated historic structures also present development opportunities. Such adapted structures can contribute significantly by simultaneously serving as living reminders of the past, can be used in the present as, for example, housing or commercial space, and create future heritage resources that fully recognise the layered complexities of our cities and their inhabitants.

Figure 2: Aerial view of the National Herbarium, circa 1955[7]

While we should always try to conserve as much of the tangible foundations of our cities, it is perhaps more significant to preserve the historical layers and the stories of the transformations of places by leaving traces of the past and adapting to something new. Unfortunately, these opportunities are often sadly missed. Heritage structures are destroyed in the name of modernisation or left to decay and ultimately destroyed without much care, as in the case of the Union Building greenhouses, which could have been the bases for a friendly Coffee Shop that contains a part of the story of how the city’s botanical and horticultural traditions developed.

Approximately sixteen kilometres away on the outskirts of Pretoria, similar developments in the botanical and horticultural traditions of Tshwane are presented by the Mothong African Heritage Trust in Mamelodi (MAHT), a hilltop refuge and heritage centre restored from an illegal dump site, by citizen activist and traditional healer, Ephraim Mabena, from the 2000s onwards.[8] It is now dedicated to the preservation and transfer of indigenous knowledge about biodiversity.[9] Although not as developed and tangible as the Union Buildings, the landscape of the MAHT is equally complex and layers the greater Tshwane landscape with other ‘culnatural’ features of heritage value.

When Mabena speaks about his journey in rehabilitating the mountainside into an indigenous knowledge, heritage and educational centre, he often considers the mountain a sacred place. During a visit to the site, I was reminded how knowledge systems often intersperse with natural landscapes and leave little to no tangible features to be identified or characterised. Even though the UNESCO definition of cultural landscapes incorporates intangible narratives in the form of beliefs “in the minds of communities”,[10] I was struck by the realisation that this may not be as acutely practised in a European context as part of the lexicon of the HLC. HLC as an approach is flexible enough to allow for, for example, the digital mapping of intangible narratives to a geologic location that creates a palimpsest ‘culnatural’ feature.

Although undoubtedly partially a product of the historical planning of Pretoria and Mamelodi’s peripherality, a tangible remnant of segregation in South Africa, the divergent treatment of the two heritage sites in such close proximity can be related to the contexts and actors involved. The Union Buildings are very much a state-sponsored top-down heritage management approach that evolved formally over a century of legislative practices informed by various socio-political and historical contexts.[11] In contrast, the MAHT is a community-led bottom-up approach of more recent origin, perhaps in response to a vacuum of formalised heritage management practices and the peripherality of the site.

Current discourse repeatedly refers to western practices as inadequate and indigenous practices as favourable, as if these are mutually exclusive concepts. Does Europe not also have indigenous knowledge regarding its natural landscapes? Are the developments in managing heritage resources by the Western world not also valuable contributions to the field of heritage management, with the recognition that all processes and science constantly change and improve? Is there no place for more “traditional” Western techniques in Africa? And vice versa? Is this not the true development of a scientific field, the investigation of ideas and techniques and their appropriateness to different scenarios?

Heritage is complex and layered. Aside from their aesthetic qualities in an increasingly monotone style of modern built environments, historic structures, for example, serve as tangible manifestations of the histories, stories and myths that symbolise places and the identities of people that created and inhabit such areas. However, so are some natural features and their associated stories.

[1] C.R.E., Rencken, Union Building, Bureau for Information, 1989, p. 30; Department of Public Works and Union Buildings Architectural Consortium, “Pretoria: Union Buildings: Conservation Management Plan”, 2007, p.22.

[2] C.R.E., Rencken, Union Building, Bureau for Information, 1989, p. 30.

[3] Department of Public Works and Union Buildings Architectural Consortium, “Pretoria: Union Buildings: Conservation Management Plan”, 2007, p.22.

[4] The Heritage Portal, “1920s Iron and Glass Structure at the Union Buildings Demolished”, 6 April 2016, <https://www.theheritageportal.co.za/thread/1920s-iron-and-glass-structure-union-buildings-demolished>, Accessed November 2022.

[5] M. Coetzer, “Union Buildings: Heritage building illegally demolished will remain so”, The Citizen, 20 October 2022, <https://www.citizen.co.za/news/union-buildings-heritage-building-illegally-demolished/>, Accessed November 2022.

[6] T.W. Honiball, “Elandspoort 357-JR”, MArch(Prof) Dissertation, University of Pretoria, 2010.

[7] F. Stark (ed.), Pretoria One Hundred Years 1855 – 1955, City Council of Pretoria, Pretoria, 1955, courtesy of Liezel Smit at the Tshwane Heritage Research Centre.

[8] C. Ntuli, “Mamelodi’s Mothong Heritage Site a university of nature for local schools”, IOL, 23 September 2020, <https://www.iol.co.za/pretoria-news/news/mamelodis-mothong-heritage-site-a-university-of-nature-for-local-schools-741ba946-a055-42da-9b18-301b6befa2c2>, Accessed November 2022.

[9] C. Ntuli, “Mamelodi’s Mothong Heritage Site a university of nature for local schools”, IOL, 23 September 2020, <https://www.iol.co.za/pretoria-news/news/mamelodis-mothong-heritage-site-a-university-of-nature-for-local-schools-741ba946-a055-42da-9b18-301b6befa2c2>, Accessed November 2022.

[10] UNESCO, “Cultural Landscapes”, <https://whc.unesco.org/en/culturallandscape/>, Accessed November 2022.

[11] N. Ndlovu, “Legislation as an Instrument in South African Heritage Management: Is It Effective?”, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, 13 (1), 2011, pp 37-57.

About the author

Hannes Engelbrecht is a PhD scholar and lecturer at the University of Pretoria, South Africa. This Blog post is based on his PhD research and inspired by his participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”, October 2022.

Contact Hannes Engelbrecht: hannes.engelbrecht@up.ac.za

About the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme

Are you interested in participating in the next iteration of the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”?

Contact Niels van Manen: n.van.manen@vu.nl.