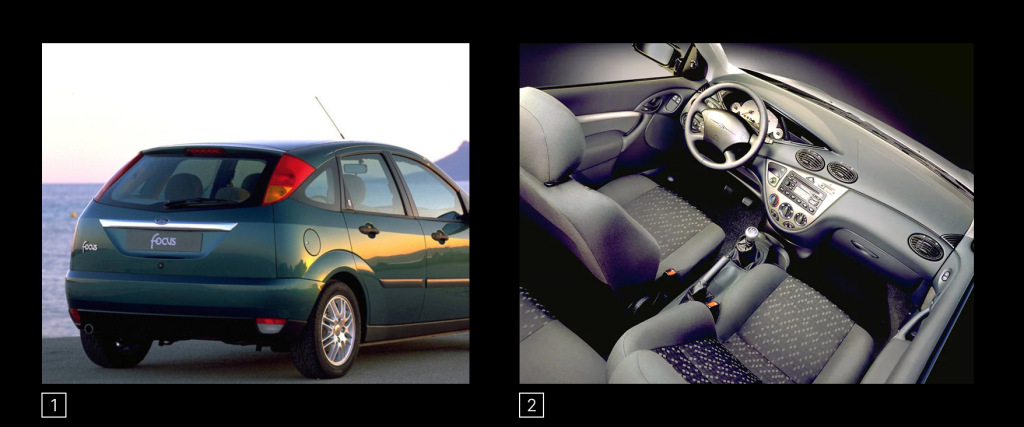

Having spent some 30 odd years on this planet, I am feeling more and more like a little 1998 Ford Focus MK1 dropped in the midst of an ocean of shiny hybrid SUV-s – quirkily cosmic, definitely modern, but not as cutting-edge as I used to think of myself even a couple of years ago. I am still too young to qualify for a historic license plate but too old to feel like I live in the present and focus on the future. Rather than that, I am balancing on the increasingly nostalgia-laced construction of an idyllic past that I cannot recognize in my urban surroundings anymore. This state offers me two options or jumps – one, to the side of the past, granting that I will become a cranky complainer; the other, right into the flow of current changes, forcing me to accept the evolution of my dear urban space. Or can I maybe find a secret passage between these two worlds and enjoy both of them equally? I would argue that this bonus option is precisely what a heritage discourse should offer to embrace change.

Digging themselves out of the tackily made graves of post-industrialization, many cities look into the future by constructing gloriously overscaled, semi-necessary and often socially disruptive projects destroying what previous generations deemed important. In the case of Liverpool, such change led to the revoking of its UNESCO World Heritage status, but there are far more similar examples that did not meet with equal outrage from the international heritage community. Of course, it is hard to deny that a botched redevelopment of a post-industrial complex somewhere on the central fringes of Europe is as difficult to swallow as introducing copious amounts of glass and steel into the dusty and rusty emptiness of a once powerful British port which now seems to be screaming “KEEP OFF OR I’LL GIVE YOU TETANUS”. No one will deny that. Yet, for those either balancing between the past and the future, or those perpetually lost in the abyss of nostalgia, seeing a skyscraper rising above the ashes of an industrial (residential, commercial, or any other) past is usually as heartbreaking as having to see the Pier Head Ferry Terminal on the banks of River Mersey. But should it be?

In a way, change can be seen as an integral part of modernity. Those planners who passed with meat axes through so many war-torn (but not only!) cities across Europe and North America (but not only!) in the mid-20th century advocated for an imminent and drastic change in the urban fabric. Unsanitary tenements lining dingy, dark streets got replaced with the clean slate of Corbusian modernism. Yet their brick-and-mortar butchery brought not a short-lived switch to which, at first, we merrily adapted but rather a never-ending chain reaction of changes which we have been experiencing to this day. Demolitions, reconstructions, revitalizations, (thermo)modernizations, densifications, changing discourses, changing residents’ profiles, changing rents, changing memories. Wherever we go, modern cities cannot cease their fast-paced evolution. And since we have already made ourselves quite comfortable in the globalizing world, all the seismic shocks of political and economic shifts are potentially more disruptive than ever before.

Following Cornelius Holtorf (2018) understanding of cultural resilience – so meticulously intertwined with intangible heritage – is all about not being able to withstand such a change and bounce back to the previous state but rather absorbing it and bouncing forward. The nature of this bouncing forward depends strongly on the context with which we are dealing. Completely different strategies would be employed in, e.g. a flood-prone rural landscape with generations-long traditions of herding and in an urban environment with a rapidly changing employment structure. Whereas in the former, we could easily look for inspiration in traditional skillsets and construction knowledge, the latter generates much fewer tools for maintaining the tangible layer of the landscape. What we can find in such an urban context is rather a collective self-image that can “provide psycho-social support in times of need, increasing a community’s capacity to absorb disturbance” (Holtorf, 2018). Of course, as demonstrated by Amin Maalouf, whom Holtorf often quotes, overreliance on such “origin stories” and narrative-based groupings can lead to increased cultural stratification in a society dealing with a sudden change. Yet, given the constant fluidity of modern urbanity I already mentioned earlier, I would argue that in many cases, the process of self-identification as a member of a certain group cannot go very far in the past. We live in landscapes shaped by the past, but we have much less time to use it to our advantage than the previous generations. Maalouf claims that “we are all infinitely closer to our contemporaries than to our ancestors” (2012) and looking at urban heritage with this in mind, we arrive at a point where understanding and appreciating the little 1998 Ford Focus MK1 becomes potentially much more valuable in terms of developing cultural resilience than sighing with often blind admiration at a fancy 1958 Aston Martin DB4.

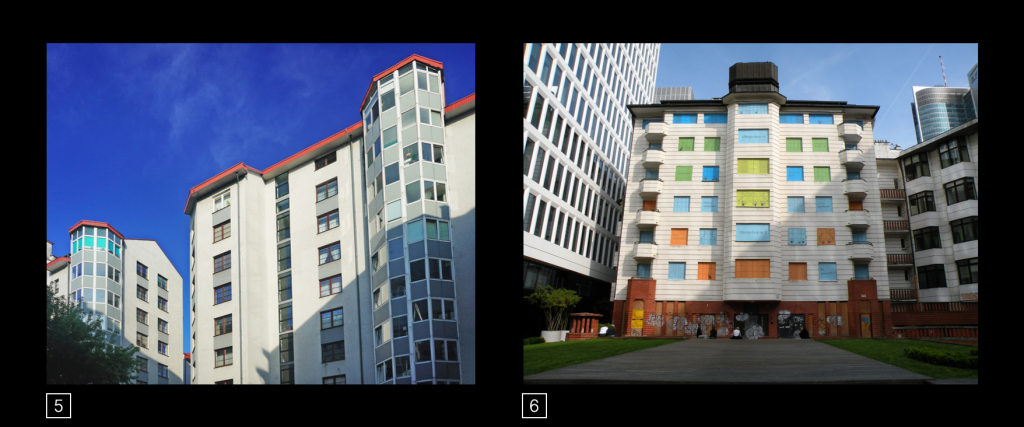

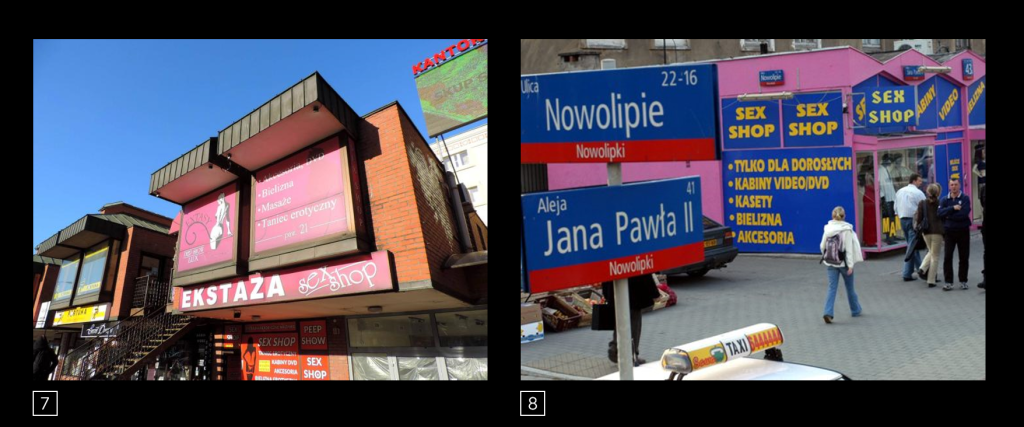

In my dearest Warsaw, one of the semi-central neighborhoods – Wola – is virtually a gigantic parking for such Ford Focuses. The history of this area goes back to the 14th century when it was established as a small, not particularly important village. In the 16th century it gained significance as the site of royal elections, being linked with the quirky period in Polish history which some, rather pompously, perceive as the first instance of modern democracy. Up until the early 20th century, bound by the tsarist fortifications, it has been developing slowly at the fringes of a still small Warsaw. Its image changed drastically some 120 years ago when it started becoming the commercial and manufacturing hub of the city that was about to regain its status as the capital of an independent Polish state. During the Second World War, parts of Wola were locked behind the ghetto walls and the district saw one of the largest civilian massacres committed by the Nazi troops in Poland. After the war, it was rebuilt as the industrial heart of the decimated city – massive factories, vast railyards, and newly constructed modernist estates found their place among some of the relics of pre-war tenement districts. Then came 1989 and changed everything once again.

For most of my life, I have associated Wola with the image of confusing emptiness. Especially as a kid, I was even scared of the gloomy atmosphere this area was oozing. One of the most vivid memories I have is that of my parents’ friends’ apartment located in an unapologetically postmodern building on Żelazna (Steel) Street. The building itself was incredibly modern – it had shiny elevators, a garage, and was even partly gated (an important status symbol in a city struggling with burglaries) – but its surroundings looked much more dystopian. Take the waiting areas of the main railway station where almost all the seats were taken by those struggling with drug addiction or homelessness (or both). Take the dimly lit passages under the incredibly wide streets crisscrossing the center of Warsaw, where the stench of urine and rust was getting mixed with that of street food, Belgian waffles, and rush. Maybe it was the sheer contrast that made my kid’s eyes so confused when it comes to Wola – among the dilapidated buildings, one could already see signs of haphazard new development, an ultra-modern office complex here, a little skyscraper there, a 5-star hotel that looked like an inside-out bathroom, and a line of old ladies selling everything, from flowers to raw meat on the sidewalk right next to it. This is where small entrepreneurship flourished in small pavilions built along wide streets. In one of them, my father got me my first computer which I did not have to share with the rest of the family. At the same time, they were becoming synonymous with all sorts of sex work and semi-illegal knock-off clothes, CDs, video games and movies, drowned under colorful signs advertising peep shows and pawn shops. As a dramatic cherry on top of this cake of this urban confusion, on a morning of March 3, 2001, three men robbed a local bank and killed all its employees making headlines across the nation. The bank was located in the very building where my parents’ friends lived. This modernity was not only confusing but also dangerous.

A couple of years later, around 2005, as a rebellious teen, I often liked to skip school and venture out on tram rides around my lovely city. Seeking adrenaline, I particularly liked to go to Wola. But now it had a lovely, big city charm, especially along John Paul II Avenue, lined with slightly fewer sex shops, even more skyscrapers, and culminating with the biggest shopping mall in Central Europe, aptly named “Arkadia”. But apart from this Manhattan-like avenue, Wola was still a bit gloomy (I also really liked going there when it was raining, so my memories are quite tainted). In some of the inner courtyards, I saw what I then eagerly dismissed as “the past”, as something that should finally change and become more like the shiny Arkadia. Over the course of the past few years, Wola has changed even more. Most of the sex shops disappeared, some of the skyscrapers built in the 1990s got demolished, and the remaining factories transformed into office parks or expensive residential areas with food courts serving prosecco and shrimps amid the red brick of former breweries. All of that accelerated by the opening of the second line of Warsaw Metro which now pumps office workers out of its underground passages right into the wide-open jaws of a Dubai-worthy Warsaw Spire building.

I recently visited Wola again and discovered something curious – despite all the changes, it still has the same aura of utter confusion as back in the 1990s. Scratching my brain to activate the cells responsible for heritage, I quickly understood that Wola is absorbing the disturbances of evolution so skillfully, that it becomes a disturbance in itself. Indeed, the gloomy courtyards are still equally gloomy, but this gloominess is not synonymous with danger and past, as I once thought. It is confusingly cheerful. A recent exhibition at the Wola branch of the Museum of Warsaw seemed to confirm this trope – Wola’s residents are proud of how their neighborhood epitomizes the changes occurring in the city. The exhibition and the activities linked to it also revealed that many residents are worried about the lack of proper incentives to preserve the fluid nature of the neighborhood. Indeed, how could one preserve something that is constantly evolving? Something that bases its own identity in change?

As disappointing as it may be, I do not have an answer, but I think I would like to find one relatively soon. In the end, while the marvels of postindustrial transformations are gradually deemed unimportant and unauthentic, the heritage community is still in the process of embracing the legacy of industrialization. In this rapidly evolving urban world, we do not have decades to ponder on the cultural value of landscapes that can help in absorbing any future disturbances. Should we hide our little 1998 Ford Focus behind a glitzy waterfall of Aperol spritz in one of the already outdated office complexes of the turn of the century? Or should we, as a professional community, try to absorb the disruptions by focusing on the changes rather than preserving urban past? In the end, “we are all infinitely closer to our contemporaries than to our ancestors” and we should start thinking about their heritage with equal care as we do about that of the previous generations.

Sources

Holtorf, C. (2018). “Embracing change: how cultural resilience is increased through cultural heritage.” World Archaeology, 50:4, 639-650.

Maalouf, A. (2012). In the Name of Identity. Violence and the Need to Belong [1996] New York: Arcade.

Dziano, J., Kępka-Mariański, W., Wywiał, I. (2015). Warszawska Wola, co było, co jest, co pozostanie. Magia Słowa.

Brzostek, B. (2021). Wstecz. Historia Warszawy do początku. Muzeum Warszawy.

Images

- Ford Focus MK1, 1998, hatchback version. Source: Wikimedia Commons

- Interior of a Ford Focus MK1, 1998. Source: autokult.pl

- Late 18th century tenement, ul. Waliców 14; partly destroyed in 1944, unoccupied since 2009. Source: Wikimedia Commons

- Gas container, ul. Kasprzaka 25; built in 1886-87. Source: Polska Pofabryczna

- Residential complex, ul. Żelazna; built in 1995, site of the 2001 bank robbery and my parents’ friends’ apartment. Source: Aleksandra Stępień-Dąbrowska, ARCHIwum Warszawy lat 90.

- Residential building, ul. Icchoka Lejba Pereca 1a; built in 1994, demolished in 2018 to make space for a new office building. Source: Aleksandra Stępień-Dąbrowska, ARCHIwum Warszawy lat 90.

- Two sex shops in a pavilion complex lining al. Jana Pawła II; built in mid-1990s. Source: Wikimedia Commons

- Corner of Nowolipie and al. Jana Pawła II with a large sex shop in a temporary commercial pavilion; built in mid-1990s. Remodeled in mid-2010 and currently occupied by a restaurant. Source: Wikimedia Commons

- Cover Image: Wola in 2021, vicinity of Rondo Daszyńskiego metro station. Source: Reddit (uncredited)