The setting

Recent years have brought a real revolution to the ways we (both, professionals and mere mortals) think of the post-war architectural heritage. An ever-growing number of concrete enthusiasts managed to stir some of the negative narratives on modernist architecture and put it in a new, much more favorable light. This contributed to the successful preservation of many stellar examples of international style, brutalism, or futurism practically all around the world. The eruption of interest towards these types of buildings generated by the initially narrow communities, led to the identification of new architectural icons, recognizable by all those claiming to be interested in architecture – London’s Barbican Centre, Montreal’s Habitat 67 or the Yugoslav Spomeniki.

Quite paradoxically, this concentration on the icons, even if improving the general knowledge about post-war architecture, overshadows the everyday examples of late modernism – housing estates, shopping arcades, or sports facilities – leaving them in the frontlines of the attacks of the opponents of this architectural format. Let me use an example: Habitat 67, being objectively an out-of-the-world marvel, when put next to a typical, Eastern European apartment building from the same era, crashes it with its largesse, aesthetic grandeur, and finesse (add more French-sounding nouns which do not apply to a simple concrete slab). It is almost as if we were to compare The Dakota building to a simple Gründerzeit tenement, built in the second half of the 19th century somewhere in the German Empire.

The Dakota in New York City, source: Wikimedia Commons

Typical tenement district in Vienna, source: Stadt Wien

The former is an undeniably good example of historicism, whereas the latter is not much more than a mere replication of the buildings it is surrounded by. Despite these differences, the importance of the simple tenement trapped in the rubble of a German city is seldom underestimated – in the end, it has witnessed so many societal changes, it hosted so many dwellers, that it is treated as a historical testimony in its own right. Contrary to this, a late modernist housing estate is still portrayed as a drab, violence-inducing, and woefully uninspiring environment that should be best demolished and replaced with something “more humane.” I think that this label, so nastily glued to the concrete giants is, to put it simply, unjust. The main reason for it, is that even if these multi-family buildings are indeed gigantic and brut from the outside, they have an equally impressive and fluffy inside. And this will be the topic of this blog entry.

The disclaimer

For the sake of clarity, simplicity, and my inner need to vent out, I will focus on one city, the second closest to my heart – Warsaw. Nevertheless, the following rant, together with the arguments used in it, can apply to many other contexts.

The problem

The housing estates dotting the urban fabric of Warsaw have never had a particularly easy life. At their conception, they were faced with all sorts of industrial and economic shortages. Then they went through a period of imported ghettoization in the 1990s, only to reemerge semi-victorious at the beginning of the new century, dressed in pastel-colored Styrofoam cladding and ready to face some new battles.

The most prominent ones being probably the rampant, money-induced densification, and the never-ending hysteria brought by the adherents of the so-called “historical lens,” who don’t shy away from putting an intimidatingly huge equation sign between hardboiled communism and the housing built between 1956 and 1989.

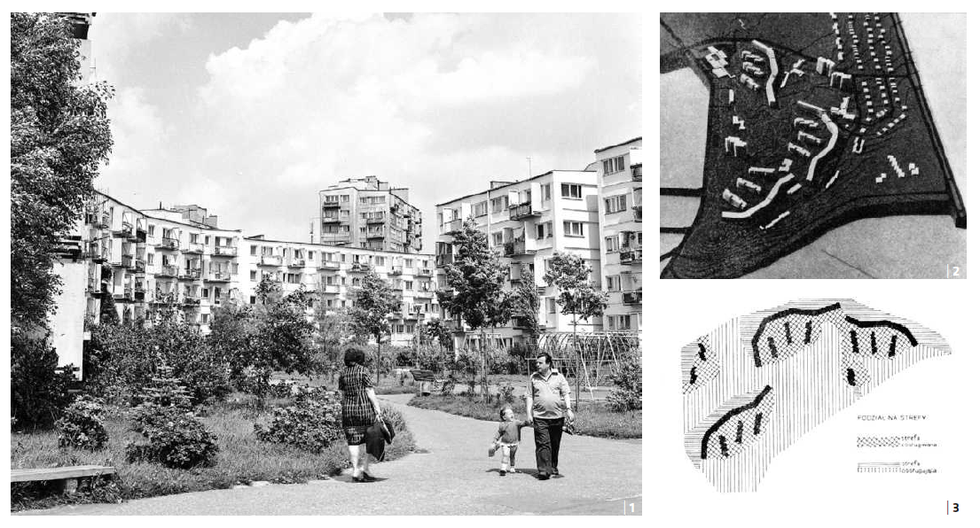

Yet from a more heritage-based perspective, the problem is much more in line with what I have written in the previous paragraphs. The ways we discuss Warsaw’s modern heritage is grounded in our obsession with architectural icons, starchitects, and photogenic buildings – after all, heritage created tourism, and tourism created Instagram, and Instagram pushed our self-obsessed culture to the limits of human imagination. It is then not very surprising that we tend to focus our attention on the biggest, the best, and the most (insert any adjective). These tropes often bring us to real gems, in terms of both their architecture and their highly functional social structure. Let’s take a look, for instance, at Halina Skibniewska’s intimate Sady Żoliborskie estate – immersed in the pre-existing, almost wild orchard, this collection of blocks, ranging from 4 to some 10 stories high, has been re-discovered by architectural enthusiasts already at the beginning of the 21st century and has remained one of the most sought-after addresses in this part of the city ever since.

On the other side of the coin, we can take a look at Oskar Hansen’s (the main starchitect of socialist Poland) vertigo-inducing Przyczółek Grochowski – still very much cherished for its interesting design, photogenic likeness to a labyrinth, and a surprisingly pretentious theory behind its form, it is far from beloved by the majority of its own residents.

Similar discrepancies can be found in many other Polish cities, notably in Lublin, where a housing estate designed by Oskar and Zofia Hansen (the same ones responsible for Przyczółek Grochowski) is an object of pilgrimage, whereas adjacent estates, much less provocative in their form, attract significantly less attention from the outside, simultaneously enjoying more love from those who live there.

The mundane

These simple juxtapositions between the iconic and the mundane point out to the fallacy of the obsession with the form, making it clear that the evolution of heritage interests from purely tangible to intangible is needed even in the more modern cases of architectural expression. Sadly, heritage professionals, highly influenced by the narratives of failure coming from the North America and Western Europe, still have a hard time treating these mundane contexts as testimonies of the (recent, but nevertheless) past.

Because this is precisely the biggest merit of these painfully normal residential landscapes of the second half of the 20th century – they collectively form the most “authentic” testimony to the past. They are able to tell the story of how Eastern European cities were reconstructed after the war damage; they testify to all the hardships and cheerful absurdity of the planned economy; finally, the changes they were subject to since 1989, showcase the ways in which the entire urban society of Poland responded to the rapid socio-economic shifts triggered by the fall of communism. In all truth, such “regular” buildings and urban landscapes are much closer to the experience of the vast majority of Poles than those considered extraordinary – often conceived by way of highly selective, even international architectural contests. It can be argued that these mundane buildings reflect the real and attainable ambitions of the people, not more grandiose expressions of the state’s might and belief in the bright future.

The mundane and its landscape

Another interesting aspect of such mundane architecture is the fact that it so perfectly encapsulates the idea of socialism that even its own form cannot be treated seriously without looking at an entire landscape it managed to create. And the importance of these “collective” everyday landscapes lies, among others, in their ability to counter the rather destructive forces of what David Harvey would call neoliberal forces – developers looking at how to squeeze as much as possible from the ample green spaces in which the modernist housing estates are almost always immersed. If treated as single buildings, these structures are not important enough to raise any alarm when a new development puts their immediate vicinity at risk. This is what happened in the largest prefab district of Warsaw – Ursynów – some 15 years ago. One of the most beloved green fields spanning between the buildings of Cybisa Street got replaced by a construction site of a massive new residential complex (of which construction is still ongoing due to various administrative mishaps, financial crises, etc.). Despite the original buildings being 10 stories high, this “intrusion” into the urban fabric brought nothing but havoc and destruction of the green idyll loved by all the residents of the estate.

Cybisa Street development in Ursynów, Warsaw, source: MAL-BUD-1

Supersam in Warsaw, source: Zbyszko Siemaszko]

Another, much more prolific example of what a destruction of modernist buildings can actually signify for the city as a whole, came in 2006, with the demolition of Supersam – Poland’s first supermarket, housed in a futuristic structure with cantilevered roofs resembling what I always imagined to be a gigantic paper napkin falling from the sky. It was one of these iconic buildings, but it gained this status only after it disappeared, being the first of many similar buildings to follow the same fate. Despite being iconic, I think it is worth mentioning it here, because of how its replacement – this time resembling an overscaled toilet on a catafalque – confused the entirety of the surrounding urban fabric. Not only it created an unnecessary visual dominant for the neighboring square, surrounded with some of the tallest tenement buildings built in pre-war Warsaw, but, most tragically, it disturbed one of the city’s most cherished vistas – the view from the Łazienki Park towards the top of the Vistula Escarpment on which the Belvedere Palace is located.

Currently, this view, although still picturesque, looks somewhat grotesque. It truly is as if we were staring at a family portrait on which a 6’5 feet clown was perched just above the grandmother’s head. The singular building, iconic or not, is just a piece of a puzzle, and modernist urban planning, with its large spaces, so often lambasted by the critics, is much more fragile than we would tend to think.

The wishful thought

Why did I actually write all this? Mostly because I feel that heritage perspective can be the answer to address the issue of late modernism in a sensible, sustainable, and egalitarian way, but is still somewhat far from being accepted as such. Of course, one has to be fully aware of the local contexts, and the one I focused on here is – thankfully – a rather easy one. There are no significant socio-economic dichotomies between the residents of housing estates and those living in the more “traditional” settings[1]. Poland still being a surprisingly monotonous country, ethnically speaking, there is little question of cultural differences or (c)overt discrimination towards specific ethnic groups. On top of that, because of the sheer scale on which Polish cities rely on this type of housing, there has never been an option of letting these buildings fall into disrepair. Despite what many may say, Polish housing estates are in good health, both physical and mental. This constatation brings me to concretize one of my dearest wishes: to convince Polish professionals that they have a unique chance of paving the road for the development of modern cities.

There is no better way to accomplish this, I think, than by turning away from planning and architectural perspectives and looking at the phenomenon of housing estates from the heritage perspective. This one, gives a great opportunity to look at the very essence of what constitutes these housing estates so well-functioning – their inner fluffiness, filled with personal stories, memories, and ripe with intergenerational wisdom. I would even go as far as claiming that these repetitive concrete structures (and their surroundings) form the backbone of the genetic code of modern-day Poland, as it is precisely there where the contemporary culture has been shaped, where the references we all understand came from, and where the positive and negative aspects of our past, present, and future intermingle. In many respects, Polish housing estate can epitomize the ongoing shifts in the heritage profession, help repairing the negative aura surrounding modernist architecture, and, advancing the domains of critical urban planning and heritage studies, contribute to the general well-being of all the cities in which this type of architectural form is present. All that is needed, is a little push in the right direction.

[1] In terms of the omnipresence of post-war housing estates in Poland, they can actually be perceived as the “traditional” residential setting.