Picture: Landscape as cultural heritage, central Italy (by Marta Ducci)

Marta Ducci, Ellen Woudstra, Gert-Jan Burgers

A main pillar in the HERILAND research on “democratization” is citizen engagement: involving citizens in landscape planning by taking into account their views and their perceptions. In doing so, we could learn from the ideas of two urban theorists: Jane Jacobs and Kevin Lynch.

In the 1960s, American cities were booming. A fast urban development was necessary in order to house the growing population. Huge urban renewal plans were developed, leading to a homogenization of the cities, a car-oriented development, the destruction of old city centres and working-class neighbourhoods. Jane Jacobs (1916-2006), an American journalist, author, and activist , best known for her book The Death and Life of Great American America Cities (1961) tried to fight these developments, arguing that urban renewal did not respect the needs of city-dwellers. She stood up against city authorities and planners, fighting for something that, today, we would define as people’s cultural heritage: “For Jacobs, cities were more about people than buildings and grand designs”.[1]

Jane Jacobs’ ideas led to the emergence of the so-called Jane’s Walks, community-led walking conversations that take place every year in hundreds of cities around the world. [2] During Jane’s Walks, people are encouraged to share experiences and stories about their neighbourhoods, as well as to discover unseen aspects of their communities. Walking is used as a way to connect people with their neighbours, offering a more personal view on the local culture, the social history and, furthermore, spatial and planning issues faced by residents.

Jane Jacobs’ approach could actually be labelled as a bottom-up participatory method. Unlike many formal top-down participatory methods used by urban planners and authorities, it may offer a better understanding of people’s perceptions of their living environment.

Jane Jacobs

Jane Jacobs’ house

Kevin Lynch

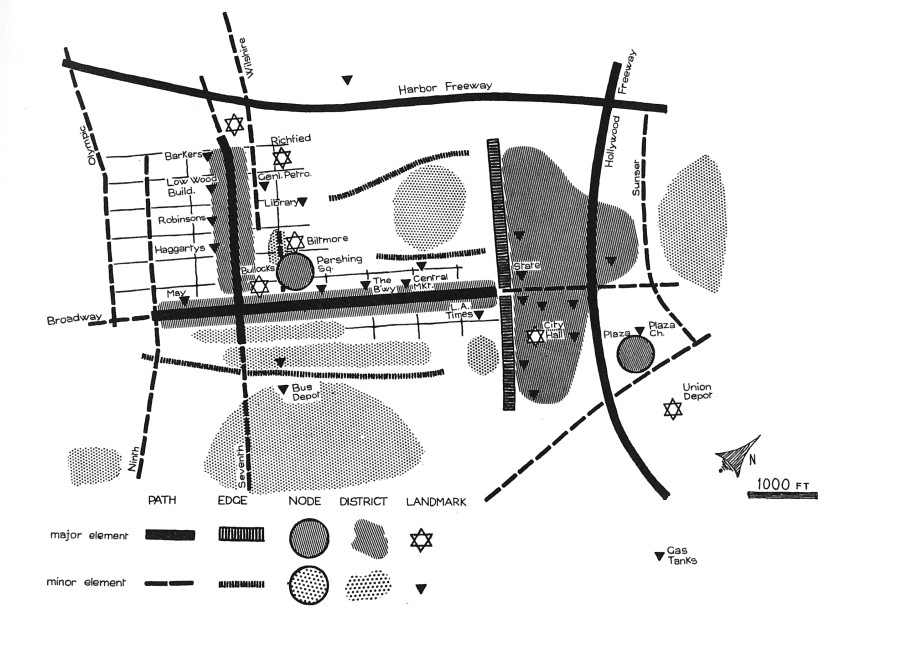

If we recognize Jacobs’ methods as useful in the practice of planning, we might also consider the concepts of Kevin Lynch (1918-1984), an American urban planner and author, best known for his work on the perceptual form of urban environments. In his key publication The Image of the City (1960), he designed maps and theories that focused on people’s perceptions, on their mental maps of the cities. He described users’ representations of the perceptual form of urban environments, creating mental maps based on five elements: paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks, giving different weights to every element. Lynch’ conceptshave had an important influence in the fields of planning. This type of analysis can, in fact, be used to monitor, in a bottom-up approach, people’s perceptions of their environment. This perception can subsequently be used by planners for the planning and design of urban structures.

Kevin Lynch’ perceptive approach is quite common in an urban context, but uncommon in non-urban landscapes. [4] The latter are usually approached from a more functionalist point of view, with an eye to the needs of infrastructure, agriculture, industry, tourism or recreation.

Few scholars and professionals pay attention to people’s perceptions of and identity bonds with landscapes the way Jane Jacobs and Kevin Lynch did. A different perspective, however, is provided by the Italian scholar Salvatore Settis, who emphasizes people’s emotional bond with landscapes and defines landscapes as a common good, a cultural heritage, owned by everyone. Settis’ approach is aligned with the approach proposed by both the European Landscape Convention and UNESCO [5].

This new vision of landscape planning may strongly benefit from the insights of Jane Jacobs and Kevin Lynch. Instead of being based only on expert’s judgements [6], people, who are actually living in its surroundings, should be involved: their perceptions and their wishes should be the basis for decision-making.

Notes

[1] Glancey J. (May 2017). The woman who saved the old New York, BBC Culture

[2] Source: https://janeswalk.org/

[3] Lynch K. (1960). The Image of the City, Harvard: MIT, 1960

[4] Referring to the UNESCO concept of landscape as cultural heritage (1992)

[5] See the concept of Cultural Landscape of UNESCO, The same concept is developed and sustained by the European Landscape Convention of the Council of Europe (2020)

[6] See, for example, the research by Peter Verburg on Landscape values and perceptions. Understanding of landscape values is an essential means to support sustainable land use and spatial planning by citizen participation.