Figure 1. Shows a comic about an architecture student by Tristan Comics. (tristancomics, 2019).

by Hend Yassin

In a world fascinated with extra-large trendy projects, it made me rethink if the extra-small tactical interventions can collectively achieve the urban biomass of an XL strategy (Lydon & Garcia, 2015).

During the Heriland training program in Amsterdam, participants were assigned one day to visit and learn about different historical areas within Amsterdam including the attractive historic landscape, “Marineterrein”.

Marineterrein (the Navy Yard) is a historic 14-hectare area built in 1655 as a construction site for warfare ships. In 1915, it became an education and training centre for the Dutch Royal Navy. For almost 350 years, it was sealed off from the rest of the city. In 2013, the Dutch Ministry of Defence began to vacate parts of the area, to be accessible to the public and developed into an innovative city quarter (HUB-IN, 2022).

The visit to Marineterrein, followed by a discussion concerning its current use as a creative Hub and its aim to be a future-proof city district, inspired me to question: why are we -as architects or urban planners- mostly strategy-driven? Even during my university education, I can’t remember that someone tried to highlight the value of temporary structures or the art of developing interim ideas instead of mastering body-building architecture.

About this Blog series & the Heriland Blended Intenstive Programme

The Blogs in this series (March-July 2024) were written by graduate students and early career professionals who participated in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Heritage and the Planning of Landscapes” in October 2023 in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Are you interested in participating in the next iteration of the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme, “Heritage and Landscape Futures”, in Gothenburg, Sweden, in October 2024?

So, it makes perfect sense when you look at your surroundings that you notice the fierce competition between mega structures. Welcome the UAE Burj Khalifa, say hello to the new Iconic Capital of Egypt, and greet the KSA NEOM Land of Future, which are the results of architects and planners practising what has been taught for decades.

Then, here comes the second question: For whom are these XL projects?

“If they were people-centred they would have never been that big in the first place!”

The population is undoubtedly increasing globally at a rapid pace, but are we in need of new high-tech mega structures to adopt the increasing number of urban dwellers? Aren’t there a lot of underused spaces within our already existing urban fabric, which are a priority to be filled -with creative uses that could match the needs of digital-driven generations- before developing new ones?

In urban landscapes, particularly historical ones such as Marineterrain, various spaces can become outdated, vacant, or underused. These spaces often fail to meet modern requirements and adapt to users’ needs, due to the rapid changes that cities undergo, urban development, and the fast growth of technology (Tanrıkul & Hoşkara, 2019). This phenomenon creates a significant gap between the past and present, reflected in the decay of the historical urban fabric (Sharghi et al., 2018). Even new developments would cause further urban voids, putting the historical urban landscape under more threat.

However, these vacant spaces can be considered as opportunities instead of challenges. They could act as stages for testing creative new ideas and temporary interventions to bridge the gap between the past and present, while paving the paths toward future sustainable urban development. In other words, they are opportunities for tactical urbanism.

Tactical Urbanism is “an approach to neighbourhood building and activation using short-term, low-cost, and scalable interventions and policies” (Lydon & Garcia, 2015). From a blank wall to an overly wide street, the opportunity to apply tactics is readily available. The actions of tactics vary in scale from the micro to macro, and can even reach the scale of a city planning (Abd Elrahman, 2016).

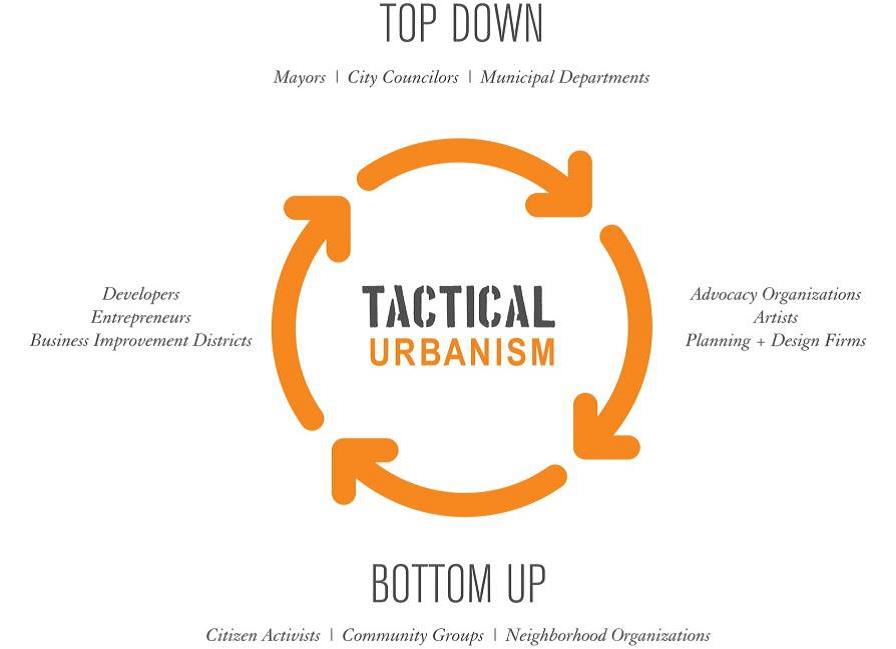

It can also be used by diverse actors, or tacticians, ranging from the governmental and institutional (Top Down) to the individual or group of citizens (Bottom Up), and everything in between, to improve an existing situation or even initiate new ones (Lydon & Garcia, 2015). Moreover, tactical urbanism is the tool, which could bridge the gap between the bottom-up and top-down, by creating a positive setting for both actors (Yassin, 2019). The following figure shows the different tacticians.

Short-term interventions are the key to the effectiveness of tactical urbanism. These interventions test ideas in real time by acting as a laboratory within a city (Lydon & Garcia, 2015). This promotes a prototype on a human scale, making it easy and accurate to test and report during implementation (Silva, 2016). It provides an opportunity to create different scenarios and aid decision-making before implementing large-scale, costly, and long-term developments that may not ensure success or meet desired outcomes (Abd Elrahman, 2016).

Although it has a defined time scale, to get immediate results, sometimes the short-term intervention becomes permanent or cyclical, where the unsanctioned becomes sanctioned, due to its outstanding results. For example: open street initiatives that made people use the space in its new function, for social activities, became a cyclical event that repeats on a specific day, either within a week, month, or year (Silva, 2016)(see the following Figure).

Returning to the development of Marineterrein’s historic urban landscape, do you think that the area is already following the approach of tactical urbanism for its sustainable urban regeneration?

The approach is not new to Amsterdam, and maybe was already in action before the emergence of the term “tactical urbanism”. A great example is NDSM, a historically significant shipyard hall located on the River IJ in Amsterdam Noord, not far from Marineterrein. The NDSM was one of the sites affected during the post-industrial boom; it was vacated in the 1980s. At the same time, different parts of central Amsterdam developed expensive rental prices which led to the gentrification of the creative milieu. So, as part of a large strategic regeneration plan, the local government benefited from the NDSM as a central tactical node that could be temporarily reactivated, in an attempt to grow a wide, organic neighbourhood around the building (Sweeting, 2015).

A competition was held by the municipality to promote a successful type of reuse of the shipyard hall. The winning participant proposed the temporary reuse of the whole space over ten years, and the various temporary use frameworks were determined by the authorities, including theatre, handicraft activities, start-up businesses, and a platform for different types of performances.

“Remember The Eiffel Tower in Paris. It was meant to be a temporary installation and now is one of the most world-famous landmarks!”

On the one hand, it looks like the success of NDSM inspired the Marineterrein area where testing solutions for future-proof cities is currently taking place. A collaboration of innovators, scientists, and businesses work together to create, experiment, and execute solutions for urban sustainability challenges. Within the area, there are educational technology companies as well as a variety of start-ups. At the moment, tenants are assigned temporarily until a definitive development strategy is created (HUB-IN, 2022).

On the other hand, the redevelopment process of NDSM was an experiment with uncertainties. And, that may be considered as one of the still existing challenges. Because the risk of the future of the shipyard hall with the experimentation is unpredictable. There is currently a ten-year preservation plan, but the area’s fate is unknown (Havik & Dorina, 2020). This is important to note and learn from.

To sum up, this blog is trying to highlight the power of XS projects in the sustainable development of historical urban landscapes and that it can be a catalyst toward successful XL development. It also questions the possibility of introducing tactical urbanism to future generations as a subject and practice for the sustainable development of our cities. Finally, it clarifies its existing limitations to learn from. Now, I will leave you wondering about the future of Marineterrain’s sustainable development following tactical urbanism.

Bibliography

Abd Elrahman, A. S. (2016). TACTICAL URBANISM: A POP-UP LOCAL CHANGE FOR CAIRO’S BUILT ENVIRONMENT. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 216, 224-235. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.12.032.

BALAŸ, M. (2013). ndsm. Retrieved from MYRIAM BALAŸ: https://myriambalay.fr/ndsm/

Bertino , G., Fischer, T., Puhr , G., Langergraber, G., & Österreicher, D. (2019). Framework Conditions and Strategies for Pop-Up Environments in Urban Planning. Sustainability, 11(24). doi:10.3390/su11247204

Dejtiar, F. (2017). The architecture student through 15 comic strips. Retrieved from Archdaily: https://www.archdaily.com/804789/the-architecture-student-through-15-comic-strips

Florian, M.-C. (2022). Saudi Arabia plans 170-kilometer-long mirrored skyscraper city. Retrieved from Archdaily: https://www.archdaily.com/986129/saudi-arabia-plans-170-kilometer-long-mirrored-skyscraper-city

Havik, K., & Dorina, P. (2020). Urban Commoning and Architectural Situated Knowledge: The Architects’ Role in the Transformation of the NDSM Ship Wharf, Amsterdam. Architecture and Culture, 8(2), 289-308. doi:10.1080/20507828.2020.1766305

HUB-IN. (2022). Marineterrein Amsterdam, NL. Retrieved November 17, 2023, from HUB-IN Atlas of Heritage-led Regeneration: https://atlas.hubin-project.eu/case/marineterrein/

Lydon, M., & Garcia, A. (2015). Tactical Urbanism: Short-term Action, Long-term Change (Vol. 2). Washington, USA: Island Press.

Sharghi, A., Jahanzamin, Y., Ghanbaran, A., & Jahanzamin, S. (2018). A STUDY ON EVOLUTION AND DEVELOPMENT OF URBAN REGENERATION WITH EMPHASIS ON THE CULTURAL APPROACH. TURKISH ONLINE JOURNAL DESIGN ART AND COMMUNICATION, 271-284.

Silva, P. (2016). TACTICAL URBANISM: TOWARDS AN EVOLUTIONARY CITIES. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 43(6), 1040-1051. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813516657340

Sweeting, A. (2015). THE VALUE OF TEMPORARY URBANISM IN CREATING RESPONSIVE ENVIRONMENTS.

Tanrıkul, A., & Hoşkara, Ş. (2019). A New Framework for the Regeneration Process of Mediterranean Historic City Centres. Sustainability, 11(16: 4483). doi:10.3390/su11164483

tristancomics. (2019). Humor de arquitectura etc. Retrieved from Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/tristancomics/

Yassin, H. (2019). Livable city: An approach to pedestrianization through tactical urbanism. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 58(1), 251-259. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2019.02.005.

About the author

Hend Yassin is a PhD student in the Heritage Studies program at the Brandenburg University of Technology, Cottbus, Germany. This Blog post is inspired by her postgraduate research with a focus on tactical urbanism and urban management of cities’ Historical cores, and based on her participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”, October 2023.

Contact Hend Yassin: heindhazem@hotmail.com

About the Amsterdam Marineterrein MiniSeries

During the Heriland Blended program Multispaces Living Lab, students worked on the Amsterdam Marineterrein to prepare proposals. This is the first of three posts presenting a heritage-informed perspective on the Marineterrein, part of the historic docks of Amsterdam.