By Khandoker Upama Kabir

Back in 1947 when the British left the Indian subcontinent, Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a British lawyer, was commissioned to draw a border to divide the Indian subcontinent into two countries, Muslim-majority Pakistan and Hindu-majority India. In doing so, he created West Pakistan and East Pakistan with India in the middle dividing the country. Sir Cyril Radcliffe was by no means a local, having made his maiden voyage to India in July of the same year. As a result of this decision without consultations from the community or locals, war ensued in 1971 between East and West Pakistan after years of conflict. This might be an extreme case but it does illustrate that making decisions without involving the community in their own identities and heritage has never been sustainable or successful.

This is not to say that the process of community involvement has not been present in the heritage management field. ‘Public participation’, ‘community involvement’, ‘public inclusion’ are all terms that have been used in cultural heritage management decision-making processes, particularly since the publication of the ICOMOS Burra Charter 1979. However, the actual public participation practices have generally proven ineffective and unproductive.

The authors of the journal article “From Public Participation to Co-Creation in the Cultural Heritage Management Decision-Making Process” (Grcheva and Oktay Vehbi 2021) noted through literature reviews that the current framework of public participation in managing cultural heritage is ineffective because it has not been implemented as originally recommended by the Burra Charter.

‘’Many times, decisions are already made by the authorities and experts in advance, and the community is tricked into believing that they have any influence at all.’’

When communities are not actively and thoroughly included from the early phases of the process, this framework of heritage decision-making produces unsustainable and undesired outcomes. Many times, decisions are already made by the authorities and experts in advance, and the community is tricked into believing that they have any influence at all. This creates distrust between the community and the authorities, which has the unintended consequence of producing an unsustainable outcome. Tokenism and phony public participation processes are widely practiced as a result of authoritarian practices that make public engagement more and more superficial and routine (Carson 2008).

A new term emerged around the start of this century, ‘Co-creation’. Co-creation was initially established as a management initiative in the business sector. It highlights the importance of including user needs and suggestions in the decision-making processes. Since the 1990s, co-creation has gained popularity as a way to develop new shared values and outcomes for users (customers) and organizations (companies) (Harvard Business Review 2000; Tseng and Piller 2003). The term “co-creation” has become very popular in this context.

This transdisciplinary bottom-up methodology is now widely used also outside the business sector. Co-creation is growing in popularity because it teaches participants how to draw on one another’s expertise to find creative answers to problems.

Theoretically, bottom-up, participatory efforts were also the origin of public involvement in the field of heritage. Unfortunately, it has been observed from numerous recent practitioner statements and from the case studies of various geographies that have been analyzed (Grcheva and Oktay Vehbi 2021) that authorities often prefer to make decisions, especially about heritage matters, top-down without taking into account the communities’ needs and ignoring their direct contribution to the decision-making process.

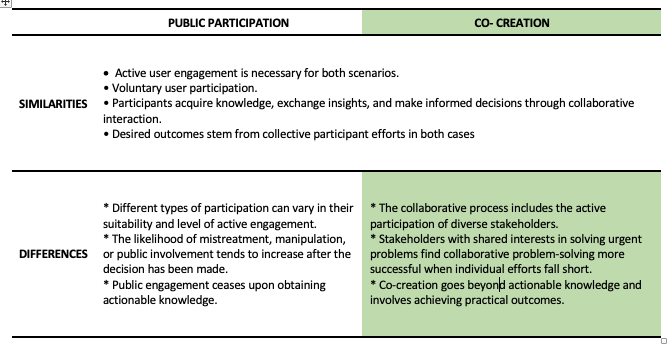

Table 1. Table showing a summary of the parallels and contrasts between the two concepts of public participation and Co-creation. (Grcheva and Oktay Vehbi 2021).

Are co-creation processes capable of producing better outcomes than public participation ones? Professor Kalliopi Fouseki’s keynote lecture on ‘Curating urban transformations through heritage and creative participation’ in the International Conference on Cultural Heritage and Spatial planning organized by Heriland in 2022 suggests they may well be. She spoke of her personal experience as a creative practitioner and researcher investigating heritage-making and community formation in the case study of Woolwich, London. Part of the Deep cities programme, Fouseki organized two creative initiatives in collaboration with a local art café called Artfix, located in High street that is a part of a wider conservation area: (1) flamenco workshops; (2) a theater play on mental illness. These creative practices co-designed with and implemented by the community helped bridge the gap between the old community and the new, who might not have met if not for these creative events. Working together in these practices was vital to capture the deep spirit of the place and create social awareness and bond between the communities with urban transformations ever changing their environment.

Another great example of what co-creation can achieve is ‘The Great Wall of Los Angeles’, where the social practitioner Judy Baca used art to bring conflicting communities together. I came across this project while doing a study project on ‘Heritage as Social Practice’. The Great Wall project aimed at telling the ethnic history of California that was selectively omitted from the history books creating a gap in the identities of the diverse community. The project involved collaboration between over 400 at-risk youth from diverse socio-economic and ethnic groups to work together to identify/ discover, recover and produce a work of art that tells the story of their heritage.

In the case of Fouseki’s project, its focus was to create interpersonal dialogue and relationship building through which the participants got to decide which part of their stories they wanted to tell. In the case of The Great Wall, the heritage production was also definitely driven by collaborative art making as it involved members of the diverse community working together to create a mural about their heritage and history. Through this project, a lot of at-risk youth learned more about their heritage and history, and through that process created a sense of belonging and identity in a place where they had previously felt unwelcome. This subsequently helped them to finish school and become successful.

Figure 1. Students and Judy Baca in front of the great wall of Los Angeles. Source: http://www.judybaca.com/artist/the-great-wall-history-and-description/

Similar examples can also be seen in rural Bangladesh where a local artist collective called ‘URONTO’ has been using co-creational practices mixed with art to create awareness and document the undocumented and neglected sites in the countryside. This too has shown great success and has been seen to create a sense of awareness and care amongst the community which was absent before.

Figure 2. A public art intervention by Abhimanyu Dalui during the 7th episode of the Uronto residential art exchange program at Sunamganj, Bangladesh. Source: https://urontoart.org/the-ownership/

The concept of co-creation works for a very simple reason. It’s a way in which the community works together to create something and the time and energy they invested in the process made them care for and wish to protect what they had helped create. It is an intrinsic part of human nature to feel a sense of ownership for their creations. Even though similar concepts have been there long before the term ‘co-creation’ was coined, other concepts have often still led to top-down approaches, while co-creation seems to genuinely facilitate bottom-up practices. Although it seems like a promising new concept, it is hard to say how these practices will pan out in the long run. So the question here is, are there circumstances where perhaps a more top-down approach would be suitable? For me, I do believe working with the community is a more empathetic way in understanding and addressing the needs of the region and is more sustainable in the long run. However, I think it’s also important to have an open mind and shift strategies according to the circumstances.

Bibliography

Carson, L. (2008). THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PUBLIC PARTICIPATION. The IAP2 spectrum: Larry susskind, in conversation with IAP2 members. 2, pp. 67–84.

Grcheva, O. Oktay Vehbi, B. (2021). From Public Participation to Co-Creation in the Cultural Heritage Management Decision-Making Process. In Sustainability 13 (16), p. 9321. DOI: 10.3390/su13169321.

Hardy, M. (2015). Reflections on the IAP2 Spectrum. In Max Hardy Consulting, 1/19/2015. Available online at https://maxhardy.com.au/reflections-on-the-iap2-spectrum/, checked on 10/22/2022.

Harvard Business Review. (2000). Co-opting Customer Competence. Available online at https://hbr.org/2000/01/co-opting-customer-competence, updated on 8/1/2014, checked on 10/22/2022.

Judy, B.(2022). The Great Wall – History and Description | Judy Baca. Available online at http://www.judybaca.com/artist/the-great-wall-history-and-description/, updated on 10/25/2022, checked on 10/25/2022.

Uronto. (2020). The ownership – Uronto. Available online at https://urontoart.org/the-ownership/, updated on 4/25/2021, checked on 10/25/2022.

About the author

Khandoker is a Graduate Student in Heritage Conservation and Site Managementat Brandenburg University of Technology, Germany. This Blog post was inspired by her research and based on her participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”, October 2022.

Contact Khandoker Upama Kabir: upama.kabir.mei@gmail.com

About the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme

Are you interested in participating in the next iteration of the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”?

Contact Niels van Manen: n.van.manen@vu.nl.