Figure 1. Liepiņš, Aldis, Latvian Culture Days, Ireland, May 5, 2013. Digital image. Latvian National Encyclopedia.

By Kristīne Ziediņa

“People are on the move in almost all parts of the world on an unprecedented scale, whether in a refugee crisis or through a long-term urbanization process,” states an interdisciplinary cohort of scholars who designed HERILAND, the project that is devoted to the creation of socially, economically, and reverentially sustainable future landscapes.[1] Throughout history, transnational ties between immigrant communities and their home countries are among the experiences people encounter.[2] It includes my personal understanding of heritage. I am a Latvian, was born in Latvia, was raised as a Latvian, and am currently living in the United States. I am one of more than 300,000 Latvians who live outside the homeland and a member of the community that, during the 20th century, created numerous diasporic landscapes and symbolic places that contribute to the continuity of the nation’s heritage (Figure 1).

Figure 2. Unknown, Latvia within Europe. Digital Image. Latvian National Encyclopedia. https://enciklopedija.lv/meklet/latvija

Latvia is a nation-state located on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea (Figure 2). At the beginning of 2022, there were 1 million 186 thousand residents living in Latvia. Of them, 62 % identify as ethnic Latvians who live side by side with ethnic Russians (24.2 %), Byelorussians (3.1 %), Ukrainians (2.2 %), Poles (1.9 %), Lithuanians (1.1 %), and people of other ethnic backgrounds (4.5 %). Latvia’s natural landscapes and cultural spaces are located within the historically multicultural belt that runs from north to south through Eastern Europe. Tribes that spoke proto-Latvian languages arrived on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea during the second millennium B.C.[3] The history and culture of the Latvian nation are shaped by colonial layers that started with the 12th-century arrival of German and Danish crusaders.[4] Over the following centuries, Swedish, Polish, and Russian territorial expansion influenced people who later formed the Latvian, Lithuanian, and Estonian nations.[5] Latvia emerged onto the European map after World War I. In November 1918, Latvians used the right of self-determination and proclaimed the democratic Republic of Latvia.

Figure 3. Briedis, Leons, Panoramic View of Rīga. Digital Image. Latvian National Encyclopedia. https://enciklopedija.lv/skirklis/52364-Vecr%C4%ABgas-siluets,-arhitekt%C5%ABr%C4%81

The syncretic character of Latvian culture is reflected throughout the Historic Centre of Riga, which was inscribed into the list of World Heritage Sites in 1997 (Figure 3). In Riga, established as a port town in 1201, European trade and cultural routes have long intersected. As such, Riga is a “living illustration of European history.”[6] In Latvia, heritage is protected. The state’s official list of cultural monuments has 7721 inscriptions that reflect the character of the nation’s heritage.[7] The list includes archeological sites, architecturally significant buildings, industrial heritage, artworks, urban spaces, and places related to historic events that reflect the multilayered character of the nation’s heritage. In 2020, the President of Latvia, Egils Levits, proposed to enact the Historical Latvian Lands Law. Adopted in 2021, the Law strengthens the commitment to preserve and promote the diversity of local cultural spaces and historic lands that reflect Latvian identity.

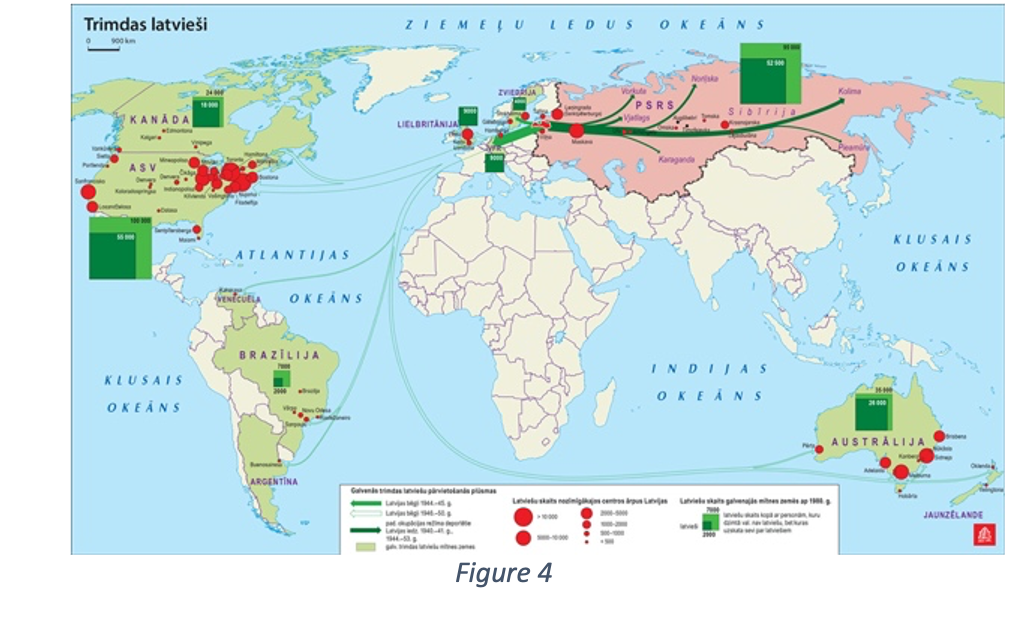

Figure 4. Unknown, Latvians in Exile. Digital Image. Latvian National Encyclopedia. https://enciklopedija.lv/skirklis/4556-latvie%C5%A1u-trimda-p%C4%93c-Otr%C4%81-pasaules-kara

People create landscapes, and these landscapes and places influence people’s values and identities.[8] What happens when the intimate relationship between people, places, and heritage is violently severed? Rodney Harrison explains that heritage is “a set of material practices concerned with anticipating and resourcing more or less distant futures in the present.”[9] Latvians, when the Soviet Union annexed Latvia (1940), during the occupation by Nazi Germany (1941-1944), and under the Soviet colonization (1944-1991), faced powers trying to prevent any possible national futures. At the end of World War II, more than 200,000 residents left Latvia (Figure 4). Abroad, they created spiritual and physical environments to contest the post-WWII notion that the assimilation of immigrants is the best solution for everyone. Even for those who settled in such faraway places as Australia, there was a hope that the Soviet colonial occupation would end and exile would take only a few years. The future that several generations of Latvians will live outside the homeland was not what was imagined, but became the reality.

Figure 5. Bolšteins, Ieva, American-Latvian girl on the shore of the Garezers. 2022. Digital Image.

The fourth generation attends Garezers (Long Lake), a summer camp located in Three Rivers, Michigan, U.S. (Figure 5). The American-Latvian community transformed the former American Girl Scout camp into a diasporic cultural landscape. Every summer since the early 1960s, American-Latvians travel to Garezers. Various programs last over several months: adults teach, children learn, and everyone enjoys a good time. “The school is standing on Latvian land,” wrote Rasma Sināte in 1965 about Garezers summer school, where diaspora’s youth learn Latvia’s history, culture and language.[10] The American-Latvian diaspora is getting smaller, but the mission and vision of the camp doesn’t not change: “Garezers prospers as a meeting place for Latvians of all ages, to nurture and educate Latvian youth, to strengthen the Latvian language, culture, and spiritual values, to promote Latvian heritage and develop links to Latvia.”[11]

Figure 6. Znotiņš, Ilmārs, Rehearsal for the concert Līgo! at the XXV National Latvian Song and XV Dance Celebration. Latvian National Culture Center. https://enciklopedija.lv/skirklis/10526-Visp%C4%81r%C4%93jie-latvie%C5%A1u-dziesmu-un-deju-sv%C4%93tki

The scale and character of cultural landscapes vary and change over time. The concept of the cultural landscape, defined by UNESCO, includes three main categories: landscapes designed and created intentionally by man; landscapes created as a response to the natural environment; and associative cultural landscapes with powerful associations rather than material cultural evidence.[12] The concept of the ‘diasporic cultural landscape’ is complex; it can include all of the three typologies mentioned by UNESCO. It also ensures the material and imaginative connections between people and physical locations in the homeland and numerous host countries. These connections can be further embodied in transnational symbolic spaces, such as gatherings, festivals, and celebrations.[13] The Song and Dance Celebration, inscribed in 2008 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity,[14] is among the national events that link Latvian and diasporic landscapes (Figure 6). Latvians abroad do not form ethnic enclaves but rather live scattered around cities.

Figure 7. Teteris, Dziesma, Latvian folk dance group Jumalīte of New York City, USA, standing in front of the Latvian Lutheran Church, Long Island, USA. 2022. Digital Image.

Historically, singers and dancers practised throughout the year in rented spaces, community centres, and Latvian churches designed and built by Latvians in exile. Currently, the digital cultural spaces, including but not restricted to Latviesi.com, Dziesmusvetki.lv, and katramsavutautasterpu.lv, help to keep the community spirit alive. According to the website dziesmusvetki.lndb.lv, since 1946, the ‘singing Latvians’ carried tradition to more than 20 places in Europe, 14 in North America, and 8 in Australia. The tradition, which was established in 1873, continues to develop. In July 2023, the XXVII Nationwide Latvian Song and XVII Dance Celebration will gather participants and an audience in Rīga, the capital of Latvia (Figure 7).

Migrants, diasporas, and refugees arrive, settle, and create transnational spaces, some barely known to the larger society of the host countries and not reflected in the homeland’s historiography.

There are numerous approaches to how people create their heritage. Some may prefer creating a new, hybrid identity inspired by the host county. In contrast, others may choose to maintain and continue the identity of the homeland. Scholars believe that diasporic cultural landscapes can provide space where intercultural communication takes place and contribute to the creation of multicultural societies.[15] Being in the middle of the Latvianness transferred from my homeland into the larger world, I found a shortage of international, national, and local policies that address transnational heritages.[16] During the HERILAND seminars, I was not surprised that practitioners and students were wondering how to link theory and practice.

What can we, heritage experts and students, do? We can describe how transactional communities created their heritage, look beyond nation-state borders, and reveal processes concealed by so-called ‘methodological nationalism’.[17] Our research should contribute to creating heritage-safeguarding policies that are easily malleable to the needs of each distinctive community, any place it is located.

[1] “HeriLand: Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes. Project Description.”

[2] For more information on transnationalism, see Linda Basch, Nina Glick Schiller, and Cristina Szanton Blanc, Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritotialized Nation-States, 1st edition ( Routledge, 1993); Steven Vertovec, “Conceiving and Researching Transnationalism,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 22, no. 2 (January 1, 1999): 447–62.

[3] Bunkśe and Tietze, “Baltic Peoples, Baltic Culture, and Europe,” 5.

[4] Annus, “Colonial Layers and the Hybridization of the Past: Layers of National Modernity in the Baltics,” 144.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Centre, “Historic Centre of Riga.”

[7] “Monument.”

[8] Rapoport, “Images, Symbols and Popular Design,” 167.

[9] Harrison, “Heritage as Future-Making Process,” 21.

[10] Garezers 25 Gados: 1965-1990, 37.

[11] AdminGG, “Mājas / Home.”

[12] Centre, “Cultural Landscapes.”

[13] Blunt, “Cultural Geographies of Migration,” 689.

[14] “UNESCO – Baltic Song and Dance Celebrations.”

[15] Yapeng and Fumo, “Cultural Landscape: Diaspora and Multicultural Community Building.”

[16] For more information on safeguarding transnational heritage, see: M. Tina Zarpour, “Challenges and Lessons Learned in Understanding Transnational Heritage,” Practicing Anthropology 31, no. 3 (2009): 24–29; Hannah Gill et al., “Migration and Inclusive Transnational Heritage: Digital Innovation and the New Roots Latino Oral History Initiative,” The Oral History Review 46, no. 2 (August 1, 2019): 277–99; Merima Bruncevic, Regulating Transnational Heritage: Memory, Identity, and Diversity, Routledge Studies in Cultural Heritage and International Law (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2022).

[17] Andreas Wimmer and Helmut K. Anheier, “Interview: Andreas Wimmer and Helmut K. Anheier,” Global Perspectives 3, no. 1 (September 26, 2022): 38287, https://doi.org/10.1525/gp.2022.38287; Andreas Wimmer and Nina Glick Schiller, “Methodological Nationalism, the Social Sciences, and the Study of Migration: An Essay in Historical Epistemology,” The International Migration Review 37, no. 3 (2003): 576–610, https://www.jstor.org/stable/30037750.

Bibliography

- AdminGG. “Mājas / Home.” Latvian Center Garezers (blog). Accessed March 26, 2023. https://garezers.org/.

- Annus, Epp. “Colonial Layers and the Hybridization of the Past: Layers of National Modernity in the Baltics.” In Soviet Postcolonial Studies: A View from the Western Borderlands. London: Routledge, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315226583.

- Basch, Linda, Nina Glick Schiller, and Cristina Szanton Blanc. Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritotialized Nation-States. 1st edition. S.l.: Routledge, 1993.

- Blunt, Alison. “Cultural Geographies of Migration: Mobility, Transnationality and Diaspora.” Progress in Human Geography 31, no. 5 (2007): 684–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132507078945.

- Bruncevic, Merima. Regulating Transnational Heritage: Memory, Identity, and Diversity. Routledge Studies in Cultural Heritage and International Law. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2022.

- Bunkśe, Edmunds V., and Wolf Tietze. “Baltic Peoples, Baltic Culture, and Europe: Intorduction.” GeoJournal 33, no. 1 (1994): 5–8. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41146192.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. “Cultural Landscapes.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://whc.unesco.org/en/culturallandscape/.

- ———. “Historic Centre of Riga.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed October 26, 2022. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/852/.

- Dove, Andrew K. “Latvians in Southwest Michigan: A Transnational Perspective.” M.A. thesis, Western Michigan University, 1997.

- Garezers 25 Gados: 1965-1990. Garezers, 1990.

- Gill, Hannah, Jaycie Vos, Laura Villa-Torres, and Maria Silvia Ramirez. “Migration and Inclusive Transnational Heritage: Digital Innovation and the New Roots Latino Oral History Initiative.” The Oral History Review 46, no. 2 (August 1, 2019): 277–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/ohr/ohz011.

- Hannaford, Dinah. Marriage Without Borders: Transnational Spouses in Neoliberal Senegal. Philadelphia, UNITED STATES: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ufl/detail.action?docID=4872121.

- Harrison, Rodney. “Heritage as Future-Making Process.” In Heritage Futures: Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices. London: UCL Press, 2020.

- “HeriLand: Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes. Project Description.” Accessed November 10, 2022. https://www.heriland.eu/project-description/.

- “Monument.” Accessed October 26, 2022. https://mantojums.lv/cultural-objects.

- Rapoport, Amos. “Images, Symbols and Popular Design.” Ekistics 39, no. 232 (1975): 165–68.

- “UNESCO – Baltic Song and Dance Celebrations.” Accessed July 8, 2022. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/baltic-song-and-dance-celebrations-00087.

- Vertovec, Steven. “Conceiving and Researching Transnationalism.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 22, no. 2 (January 1, 1999): 447–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/014198799329558.

- Wimmer, Andreas, and Helmut K. Anheier. “Interview: Andreas Wimmer and Helmut K. Anheier.” Global Perspectives 3, no. 1 (September 26, 2022): 38287. https://doi.org/10.1525/gp.2022.38287.

- Wimmer, Andreas, and Nina Glick Schiller. “Methodological Nationalism, the Social Sciences, and the Study of Migration: An Essay in Historical Epistemology.” The International Migration Review 37, no. 3 (2003): 576–610. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30037750.

- Yapeng, Ou, and Marina Fumo. “Cultural Landscape: Diaspora and Multicultural Community Building,” 2017. http://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/1983/1/10.%20ICOA%201714_Fumo_SM-with%20warning.pdf.

- Zarpour, M. Tina. “Challenges and Lessons Learned in Understanding Transnational Heritage.” Practicing Anthropology 31, no. 3 (2009): 24–29. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24781917.

About the author

Kristine Ziedina is a PhD researcher in Phd Historic Preservation at the University of Florida. This Blog post was inspired by her own experiences as a member of the Latvian diaspora community in the USA and based on her participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”, October 2022.

Contact Kristine Ziedina: kristine.ziedins@gmail.com

About the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme

Are you interested in participating in the next iteration of the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”?

Contact Niels van Manen: n.van.manen@vu.nl.