Figure 1. image of caravan in the Beauduc-dunes. source: Clément Chapillon, caravan in the Beauduc-dunes, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/m-le-mag/article/2022/08/09/everything-is-precarious-that-s-the-founding-principle-of-the-camargue-in-the-village-of-beauduc-paradise-is-taking-on-water_5992946_117.html

By Thijs Serrien

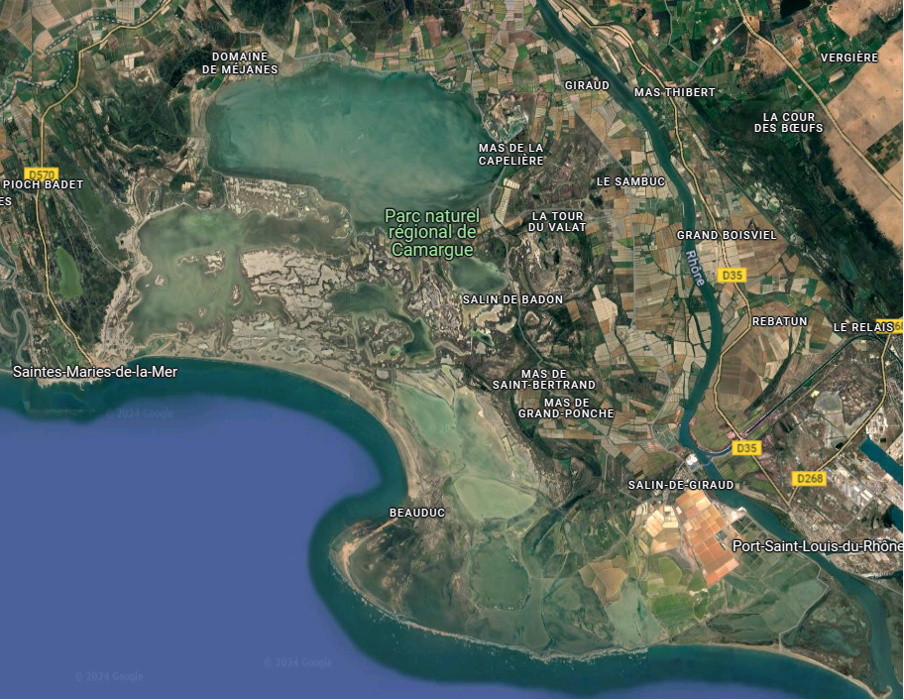

In southern France, where the Rhône River flows into the Mediterranean, lies the Camargue, a region where nature and culture intersect (fig. 2). Known for its flamingos, salt flats, and iconic horses, the Camargue faces pressures from climate change, modernization, and increasing tourism. These threats not only impact the environment but also affect the local communities and traditions that have long been part of the region. One such community is Beauduc, a small village on one of France’s largest beaches, which has evolved into a unique, self-governing enclave. But how does this kind of community coexist in a protected landscape like the Camargue?

About this Blog

This is the 17th blog post of the series of 24 blogs prepared by graduate students and early career professionals who shared their views on the future of heritage and landscape planning.

The writers of these blogposts participated in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Heritage and the Planning of Landscapes” in October 2024 in Gothenburg, Sweden.

A Living Landscape Under Pressure

Since the late 1960s, the Camargue has experienced profound changes. Traditional agriculture, such as rice cultivation and salt extraction, is under strain from both economic and environmental challenges. Tourism has also increased, bringing new pressures on the environment and local livelihoods. Alongside nature lovers, sports enthusiasts like kite surfers now frequent the region’s vast beaches, taking advantage of the wind and space.

Yet, the Camargue is not just a tourist destination—it is also home to a variety of people, in the past and still today from rice farmers, horse and bull ranchers, and salt workers to the inhabitants of a place like the Beauduc village. About 110 000 people are nowadays living in the area. This doubles in summer, demonstrating the impact of tourism.

Located on the remote Plage de Beauduc, the Beauduc-village has been a haven for alternative lifestyles since the 1970s (fig. 3). Its isolation and lack of amenities like electricity give it a distinct character, yet its existence within a protected area remains controversial. It takes more or less 45 minutes with a slightly or somewhat modified vehicle to get over the dirt road full of potholes into the village from the last stretch of asphalt. This ‘inhabited’ area consists of a more permanent village on the one hand (fig.5), and a part closer to the beach that allows more temporary holiday homes on the other, at Beauduc-Plage (fig. 4). Many campervans or people with tents also pass through here as a base for kitesurfing, for enjoying the wide-open beach or just being far removed from mainstream society.

Cultural Challenges and Heritage Conservation

The French government designated the Camargue as a regional natural park in the 1970s to preserve its ecological and cultural significance. Despite repeated government efforts to dismantle Beauduc, the village has endured. The “hut culture” here dates back to Roman times, with fishers, farmers, and others building temporary shelters from available materials. This tradition persists, though it clashes with modern views of what heritage should look like in a natural park. The way of life also creates some more pollution. Especially in the part of the more temporary habitation that involves going to the toilet near the dunes. Human presence through vehicles, for example, can also be seen as disruptive to the ecosystem. The dunes around the part where there is more temporary visitation also show signs of human presence. A wider use plan for the area has been in place since 2011. This is to reduce the negative impact on nature and landscape. On the access road, a barrier has been placed where not too wide vehicles can fit through. This should stop people from driving to the beach only with small vehicles. Large waste containers should also solve the waste problem.

Unlike the top-down management model typical in Western societies, where the state imposes rules, Beauduc operates as a self-governed community. Although still part of French territory, it feels distant from the authority of Paris, with residents deciding how their village should function. For many, Beauduc represents freedom and a return to nature, values that residents fiercely defend. The village has become a cultural phenomenon, so much so that locals established the “Association de Sauvegarde du Patrimoine de Beauduc” to protect their unique way of life.

However, the future of Beauduc raises important questions. The lack of basic infrastructure, such as sanitation, creates unsustainable living conditions, putting the balance between cultural heritage and environmental conservation at risk. The area’s growing popularity among kite surfers and other visitors further strains local resources. The region also faces economic challenges, as traditional industries like farming and salt extraction have lost their viability. Some argue that the site would be better suited for a modern holiday resort, especially given the rise in temporary tourists, despite a ban on wild camping. Aware of the impact of their lives on the landscape, the association de Sauvegarde du Patrimoine de Beauduc organises waste clean-ups to still keep their imprint as minimal as possible.

This raises a larger question: Who has the right to enjoy this landscape? Current tourism offerings—such as horse rides and bike tours—tend to cater to wealthier urbanites seeking an experience of “wild nature.” In contrast, many of Beauduc’s visitors come from working-class backgrounds, raising concerns about whether access to the landscape is equitable.

Conclusion

The future of the Camargue depends on finding a balance between environmental conservation and respecting the cultural value of communities like Beauduc. The situation invites reflection on whether current systems for managing heritage and nature sufficiently protect marginalized groups who often seek refuge in remote, natural areas. Shouldn’t these communities also have their place, and their heritage recognized?

But the Beauduc and Camargue case also shows another difficulty. Residents want to be secluded instead. So, they have no demand for government interference. Heritage tourism will not help them either as it will put even more pressure on the region.

The Camargue shows that heritage and landscape management cannot rely solely on top-down approaches. Even in seemingly small, isolated cases like Beauduc, human presence shapes the landscape. The residents of Beauduc, many of whom feel disconnected from life in large cities, have carved out a space for themselves in the Camargue. Similar communities exist across Europe and the world, operating outside formal legal frameworks but nonetheless deserving recognition. Such places also reveal how the free use of land can foster social and community experiments that might be impossible in mainstream society. For the people of Beauduc, the landscape is more than just a backdrop—it is a foundation for their way of life. In addition, it also shows that despite tourism nowadays increasingly depending on big project developers, people who do not want to or cannot depend on it are also entitled to it.

Bibliography

‘Camargue (Delta Du Rhône) – Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB).’ Geraadpleegd 29 oktober 2024.https://www.unesco.org/en/mab/camargue-delta-du-rhone.

Clarke, Alan. ‘Coastal development in France: Tourism as a tool for regional development.’ Annals of Tourism Research 8, nr. 3 (1 January 1981): 447-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(81)90008-6.

Dunlop, Catherine T. ‘Coexisting with Nature: The Huts of the Camargue Wetlands.’ Arcadia, 26 September 2019.https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8797.

‘“Everything Is Precarious, That’s the Founding Principle of the Camargue”: In the Village of Beauduc, Paradise Is Threatened by Rising Waters.’ 9 Augustus 2022. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/m-le-mag/article/2022/08/09/everything-is-precarious-that-s-the-founding-principle-of-the-camargue-in-the-village-of-beauduc-paradise-is-taking-on-water_5992946_117.html.

Grimwade, Gordon, en Bill Carter. ‘Managing Small Heritage Sites with Interpretation and Community Involvement.’ International Journal of Heritage Studies 6, nr. 1 (1 januari 2000): 33-48.https://doi.org/10.1080/135272500363724.

Minvielle, Paul. ‘La gestion d’un grand site camarguais : les cabanes de Beauduc’. Méditerranée. Revue géographique des pays méditerranéens / Journal of Mediterranean geography, nr. 105 (1 July 2005): 7-17.https://doi.org/10.4000/mediterranee.336.

Nicolas, Laurence. ‘Beauduc, une pratique habitante « insaisissable » par le politique ? De l’utopie à la normalisation’. Text. Publication TERRA-HN-editions collection SHS. Geraadpleegd 29 oktober 2024.https://www.shs.terra-hn-editions.org/Collection/?Beauduc-une-pratique-habitante-insaisissable-par-le-politique.

———. ‘Pratiques de nature populaires et écologisation du territoire:Les effets sociaux de la requalification d’un espace littoral’. Norois 238239, nr. 1 (1 november 2016): 59-67. https://doi.org/10.4000/norois.5865.

Picon, Bernard. ‘Aperçu de l’histoire socio-économique de la Camargue’. Revue d’Écologie Sup2 (1979): 31-48.

Tamisier, A. ‘The Camargue: in search of a new equilibrium between man and nature.’ Landscape and Urban Planning 20, nr. 1 (1 January 1991): 263-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2046(91)90120-B.

About the author

Thijs Serrien is a master student from the heritage studies program at the university of Antwerp. Previously he studied art sciences at the university of Ghent. This blog post was inspired by his participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Program on “Heritage and Landscapes Futures”, in Gothenburg, Sweden, in October 2024.

contact the author: Thijs.Serrien@student.uantwerpen.be